South African musical history is

characterized by local tendencies and internationl influences and it is the most

complex and developed of the country but at thesame time unique.

South African musical history is

characterized by local tendencies and internationl influences and it is the most

complex and developed of the country but at thesame time unique.Music

South African musical history is

characterized by local tendencies and internationl influences and it is the most

complex and developed of the country but at thesame time unique.

South African musical history is

characterized by local tendencies and internationl influences and it is the most

complex and developed of the country but at thesame time unique.

The first musician were San people who played instruments like drums, flutes, rattles and also their bow.

The Khoikhoi (man's man) who arrived in Southern Africa 3.000 years ago had probably a musical tradition which was more sofisticated than the San's one.When in 25th November 1947 Vasco da Gama arrived to Mossel Bay, they welcomed Portuguese people with musical performances.

In the XVII century South Africa was occupied by black african peoples who were more technologically sophisticated than San and Khoikhoi. They had an advanced musical tradition with songs for every occasion (the words chaged while the musical structure was always the same).

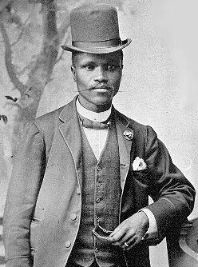

In XIX century with the arrival of

Christian missionaries African music met occidental influences and they provided

the first organized musical training in the country, bringing to light many of

the modern country's earliest musicians, including Enoch Mankayi Sontonga, who

wrote the national anthem Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika (“God Bless Africa”) in 1897

which was later adopted by the liberation movement and later became the national

anthem of a democratic South Africa.

In XIX century with the arrival of

Christian missionaries African music met occidental influences and they provided

the first organized musical training in the country, bringing to light many of

the modern country's earliest musicians, including Enoch Mankayi Sontonga, who

wrote the national anthem Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika (“God Bless Africa”) in 1897

which was later adopted by the liberation movement and later became the national

anthem of a democratic South Africa.

The missionary influence, plus the later influence of American spirituals, spurred a gospel movement that is still very strong in South Africa today. Drawing on the traditions of churches such as the Zion Christian Church, one of the largest such groupings in Africa, it has exponents whose styles range from the more traditional to the pop-infused sounds of, for instance, the former pop singer Rebecca Malope. Gospel, in its many forms, is one of the bestselling genres in South Africa today, with artists who regularly achieve sales of gold and platinum status.

The missionary emphasis on choirs, combined with the traditional vocal music of South Africa, and taking in other elements as well, also gave rise to a mode of a capella singing that blend the style of Western hymns with indigenous harmonies.

This tradition is still alive today in the isicathamiya form, of which

Ladysmith Black Mambazo are the foremost and most famous exponents.

foremost and most famous exponents.

This vocal music is the oldest traditional music known in South Africa. It was communal, accompanying dances or other social gatherings, and invovled elaborate call-and-response patterns.

Though some instruments such as the mouth bow were used, drums were relatively unknown. Later, instruments used in areas to the north of what is now South Africa, such as the mbira or thumb-piano from Zimbabwe, or drums or xylophones from Mozambique, began to find a place in the traditions of South African music-making.

Still later, Western instruments such as the concertina or the guitar were integrated into indigenous musical styles, contributing, for instance, to the Zulu mode of maskanda music.

The development of a black urban proletariat and the movement of many black workers to the mines in the 1800s meant that differing regional traditional folk musics met and began to flow into one another. Western instrumentation was used to adapt rural songs, which in turn started to influence the development of new hybrid modes of music-making (as well as dances) in the developing urban centres.

In the early years of the 20th century, the increasing urbanisation of black South Africans in mining centres such as the Witwatersrand led to the development of slumyards or ghettos where new forms of hybrid music began to arise.

Marabi was the name given to a keyboard style (usually played on pedal organs, which were relatively cheap to acquire) that had something in common with American ragtime and the blues, played in ongoing cycles with roots deep in the African tradition.

The sound of marabi was intended to draw people into the shebeens (bars selling homemade liquor or skokiaan) and then to get them dancing. It used a few simple chords repeated in vamp patterns that could go on all night - the music of Abdullah Ibrahim still shows traces of this form.

Associated with the illegal liquor dens and with vices such as prostitution, the early marabi musicians formed a kind of underground musical culture and were not recorded. Both the white authorities and more sophisticated black listeners frowned upon it, much as jazz ("the devil's music") was denigrated as a temptation to vice in its early years in the United States.

But the lilting melodies and loping rhythms of marabi found their way willy-nilly into the sounds of the bigger dance bands, modelled on American swing groups, which began to appear in the 1920s; it added to their distinctively South African style.

Such bands, which produced the first generation of professional black musicians in South Africa, achieved considerable popularity in the 1930s and 1940s: star groups such as The Jazz Maniacs, The Merry Blackbirds and the Jazz Revellers rose to fame, winning huge audiences among both blacks and whites.

So successful were some of these bands, in fact, that jealous white musicians used the regulations against racial mixing and the liquor laws (which restricted black access to "white" liquor) to hamper their progress.

Over the succeeding decades, the marabi-swing style developed into early mbaqanga, the most distinctive form of South African jazz, which has given its flavour to much South African music since then, from the jazz performers of the post-war years to the more populist township forms of the 1980s.

The beginnings of broadcast radio intended for black listeners and the growth of an indigenous recording industry helped propel such sounds to immense popularity from the 1930s onward.

Travelling variety shows, vaudeville troupes and dance concerts boosted the impact of black music, and schools began to arise teaching the various jazzy styles available, among them pianist-composer Wilfred Sentso's influential "School of Modern Piano Syncopation", which taught "classical music, jazz syncopation, saxophone and trumpet blowing", as well as "crooning, tap dancing and ragging".

A truly indigenous musical language was coming into being.

Paul Simon & Miriam Makeba

Ladysmith Black Mambazo

Paul Simon & LadySmith Black Mambazo

Hugh Masekela with Paul Simon

SOURCES:

videos: www.youtube.com

text: "SUDAFRICA", INSIGHT GUIDES,EDIZIONE ITALIANA - IL SOLE 24 ORE